Acknowledgement.

School of Yoga is profoundly grateful to Saṃskṛta scholars and academics Pijus Kanti Pal (pal.pijuskanti@gmail.com) and Dolon Chanpa Mondal for their support in Saṃskṛta transliteration and quality control.

School of Yoga explains Śrīmad-bhagavad-gītā, chapter 5, sannyāsa-yoga (yoga of renunciation).

Introduction.

- In chapters 2, 3 and 4, Śrī Kṛṣṇa guides the student from disillusionment, fear of outcome and grip of illusion (māyā) to action and then, renunciation of action.

- In chapter 5, he moves to the next step, what happens after a person has cleaned up his action (karma)? How does one evolve to the next level of personal development?

- Importantly, one must recognise that development in Yoga is experiential and everything that is said in Śrīmad-bhagavad-gītā can only create value when there is introspection and practice.

School of Yoga explains Śrīmad-bhagavad-gītā, chapter 5, sannyāsa-yoga (verse 1-6).

Jñāna-yoga or karma-yoga, which is better?

Arjuna starts off by expressing confusion – which is better, performing action or renouncing it? Śrī Kṛṣṇa says, both jñāna-yoga (sāṃkhya) and karma-yoga are one (eka) and reach the same goal, Brahman. However, the path of renunciation is very difficult and painful. In any case, even renunciation requires action, so renouncing the outcome of action is an easier method of reaching Brahman.

School of Yoga explains Śrīmad-bhagavad-gītā, chapter 5, sannyāsa-yoga (verse 2-11).

Overview.

- First, the yogī should try and smoothen internal turbulence during experience of change. This is called purification of the soul (ātmaśuddhaye). This is done by discriminating permanent from impermanent (viveka) and approaching all actions with dispassion (vairāgya).

- Next, the yogī attempts to remain in this state at all times and in all situations. This includes seeing, hearing touching, smelling, eating, evacuating, sleeping, breathing or speaking. Consequently, the cognitive apparatus (indriyas) is conditioned one to move among similar sense objects without getting affected by stimulus.

- In fact, the yogī should perform karma (activity) with sentience (awareness of his senses) withdrawn from the environment, viewing all creation as one (sama-darśana).

- Lastly, the yogī should be detached from the surroundings like a lotus leaf in water (water on a lotus leaf slides off without making the leaf wet) and remain in an isolated state. This is done by performing action using the body, cognitive apparatus, logical reasoning and senses with the attitude of not acting nor causing action.

- So, the yogī’s awareness is absorbed in the Brahman, his or her Soul is established in the Brahman and with the Brahman for the goal and nothing else. This is called ekāgratā (single-pointed focus).

School of Yoga explains Śrīmad-bhagavad-gītā, chapter 5, sannyāsa-yoga (verse 12-19).

Brahman.

- Brahman is neutral – it is neither the initiator, creator nor the doer, nor does it get attached to creation – this is because this is its innate nature. Also, Brahman does not accept from anyone their demerits or even merit, this occurs in people on account of illusion (māyā) and lack of knowledge (ajñāna).

- The reason for this delusion is that the Self (ātman) experiences existential doubt (am I alive? do I exist? who am I?) and this insecurity gives rise to the need to form bonds and attachments that reinforce a sense of existence and increase the feeling of self-worth (asmitā).

- Consequently, this need for reinforcement of its sense of identity creates a veil of ignorance (māyā) over the true nature of the Self (ajñāna) which is dispelled by knowledge of the Self (jñāna).

- Also, this makes māyā (illusion) very difficult to overcome unless the person is able to overcome the need for reinforcement of self-worth as well as distance and detach the Self from impact of the environment on the Self (ātman).

A person merges with Brahman when he has advanced in cleansing of the Soul (ātmaśuddhaye), views everything as one (sama-dṛṣṭaye), has an intellect that is immersed in an unchanging state of peace (Brahman) with complete focus on an unchanging state of peace (Brahman) (verse 18-19).

School of Yoga explains Śrīmad-bhagavad-gītā, chapter 5, sannyāsa-yoga .

The concept of karma-yoga.

- We get stimulus through our senses – sight, sound, touch, taste and smell. Then, we react through our motor organs – legs, hands, tongue, anus and sexual organs.

- Consequently, we get into a cycle of stimulus and response, that is driven by our senses, cognition and intellect. This creates an illusionary world called māyā that veils the Brahman.

- So, to merge with Brahman, we need to transcend māyā (Illusion or farce).

- One way is to isolate ourselves from the environment so that stimulus is controlled, so that impact of māyā is slowly controlled. This is renunciation (sannyāsa) and the path is called jñāna-yoga.

- The other way is to perform karma (action), but control the senses (indriyas), cognition (manas) and logic (buddhi). Consequently, during the performance of action, we remain calm, unruffled in every experience and look at effort & outcome without fear or favour. This path is called karma-yoga.

- However, both paths are difficult. In fact, isolating ourselves from society requires enormous ability to come to terms with loss of self-worth or self-esteem (asmitā).

- Also, the difficult effort of isolating the Self from society itself is action (karma).

- Therefore, whether we practice renunciation (sannyāsa) or control of action (karma-yoga), action is required. However, by practicing karma-yoga, we give ourselves the ability to improve continuously without bringing catastrophic damage to our self-esteem (asmitā) that sannyāsa-yoga could bring.

- Since the risks are lower, this karma-yoga is seen by Śrī Kṛṣṇa as more practical and thus achievable.

School of Yoga explains Śrīmad-bhagavad-gītā, chapter 5, sannyāsa-yoga (verse 18-29).

Increasing free-will (svatantra).

- To get jñāna (knowledge of the self), one must anchor the seat of cognition (manas) and seat of logic (buddhi) with the Brahman and view everything with sama-darśana (equal gaze), whether it is a learned person, a cow, an elephant, a dog or even an outcast.

- As a result of sama-darśana (equal gaze), the seat of cognition (manas) becomes spotless (nirdośa) and without bias because it allows the yogin to separate the stimulus from the source of the stimulus.

- Consequently, a sense of equality gets established and this ensures that the yogī becomes a detached soul.

- As a result, the yogī recognises all actions are born out of impulses of desire and that happiness or peace comes from removal of duality. So, the yogī reacts with equanimity to pleasant and unpleasant stimuli, being neither too happy at good news nor grieving at unpleasant news.

- Self-controlled ascetics (sannyāsin) does this by shutting out external objects, fixing the gaze between the eyebrows (nāsikāgra-dṛśṭi) and equalising their incoming (prāṇa) and outgoing (apāna) breath (vāyu) and moving it within the nostrils (nāsābhyantaracāriṇau).

Interplay between guṇa, citta, dharma and karma.

- When we are in our natural state (dharma), we experience a cognition of peace, the three attributes (guṇas – tamas = delusion / rajas = passion / satva = harmony) are in balance.

- Then, stimulus coming in through the senses (indriyas) is collated by the centre of cognition (manas). This stimulus is compared with conditioning (dharma) before a response is formulated.

- Citta (consciousness) is the medium that recognises the object, stimulates the senses, collates the data at the cognitive centres (manas), carries the information to the intellect (buddhi) for comparison with conditioning (dharma) and formulates a response.

- If there is congruence, ahaṃkāra (I am the doer) pulls the object towards it because it wants continued engagement. If there is dissonance, ahaṃkāra pushes the object away to avoid discomfort. As a result, there is give-take or a transaction.

- Any transaction or give-take results in karma (action). When there is congruence / attraction (rāga) or dissonance / repulsion (dveṣa) with the object, a give-take transaction results in pull-push movement between the subject and object. In like (rāga), the subject and object try to come closer to each other and in dislike (dveṣa), they try to push each other away.

- However, in give-take transactions karma is always unequal between the giver and taker, this results in an imbalance, since one always gives or takes more from the other. Consequently, this imbalance results in debt (ṛṇa) which has to be repaid, even if it means taking another jñāna or rebirth.

The citta (consciousness).

- Citta (consciousness) performs the following action:

- It transmits projection of self-worth (asmitā) of the subject to other entities and vice-versa,

- Also, it seeks and identifies other entities,

- Then, it relays feedback from other entities as experience,

- Citta carries the stimulus through the senses (indriyas), to the centre of cognition (manas), then to the centre of logic (buddhi).

- Then, it acts as bridge, comparing stimulus with conditioning (dharma),

- The outcome is integrated with the sense of self-worth/ identity (asmitā) which takes ownership of the response (ahaṃkāra).

- Finally, citta then carries out the response as a projection of identity (asmitā).

- In short, citta (consciousness) is the thread (sūtra) that runs across the complete transaction spectrum, from identifying another entity, acquisition of information to formulation of response, then response and finally feedback.

- One can experience consciousness (citta) flowing out of the frontal lobe when one is transacting with anyone.

- When citta (consciousness) examines itself, this internal awareness of its own existence is called jñāna.

- Next, the awareness of the projection of citta (consciousness) to the environment is called vijñāna (macro or system transaction).

- Also, the experience of citta of the Identity’s (puruṣa) projection perceived by others is called asmitā (self-esteem/ self-worth).

- Additionally, the experience of being a doer by puruṣa is called ahaṃkāra (I am the doer).

- Lastly, awareness of consciousness (citta) and its movements is called prajñā (awareness). This awareness is primordial and can be experienced with practice, when a person steps back from any situation and watches his own actions as if he or she were a different person.

- When a person focuses on the action and not the experience, there is no experience of like (rāga) or dislike (dveṣa), which results in the effort of puruṣa to project itself being nullified.

- This effort is yajña or sacrifice.

Example of citta and in daily life.

When we go to a funeral or cremation, our identity (puruṣa) has already been conditioned (dharma) about how the self-identity must be projected.

Hence, we dress and act sombre at a funeral, we are serious in a temple or church and joyous at a wedding. Similarly, when we meet a friend, we show happiness and at a business meeting, we present appropriate behavious. Finally, when we are alone, our consciousness keeps reaching out for subjects, we dream, imagine situations and sometimes reflect on ourselves.

This projection of our Self and our experiences is our consciousness (citta). The fact is, the change in our demeanour occurs because our consciousness (citta) takes on the atmosphere of the environment naturally. Consequently, citta always mirrors with the same identity as its environment to avoid damage to self-worth (asmitā).

If the individual were to behave contrary to dharma (conditioning or accepted practice), the environment will reject the projection of the individual (dveṣa) leading to psychological damage of the asmitā (self-esteem).

How should we perform karma?

Māyā (illusion) is driven by guṇa (attitude) which drives conditioning (dharma). Guṇa comprises tamas (delusion), rajas (passion) and sattva (harmony). So, we can transcend māyā and experience the nature of Self by taking the following actions:

- First, avoid hatred (tamas) and anger (rajas). Then, try to stay balanced (sattva) with sama-darśana (equal gaze).

- Next, bring the senses under control.

- Start by physically avoiding sensory stimuli.

- Also, try controlling flow of stimuli where they are collated at the cognition (manas). This area corresponds to the area around the amygdala where “flight or fight” responses are processed. One may increase one’s ability by practicing prāṇāyāma and meditation.

- Finally, practice control of conversion of stimulus to response by separating the intellect (buddhi) from conditioning (dharma) as well as logically try to redirect response to a sāttvika (harmonic or balanced) one to preventing rise of tamas or rajas.

- Also, avoid duality such as like/dislike, happy/ sad etc as these result in tāmasika and rājasika experiences which can hijack the intellect (buddhi).

- Additionally, view everything with sama-dṛṣṭi (sama = equal + dṛṣṭi = gaze), this way tamas and rajas are brought under control.

- Finally, do not get attached to action, its experience, efforts or outcome. Step back and recognise it as māyā. For example, perform action as a duty as sincerely as possible without expecting any return, avoid attachment to the action (ahaṃkāra) or outcome (phala).

As a result, senses become controlled and Self is isolated from the actions. Also, this allows clarity in cognition (viveka) and dispassion (vairāgya), the two key requirements for betterment in Yoga which allow the Soul to transcend māyā and merge with the Truth (Brahman).

School of Yoga explains Śrīmad-bhagavad-gītā, chapter 5, sannyāsa-yoga.

The physiology and awareness in verse 27.

The sanyāsin does this by shutting out external objects, fixing the gaze between the eyebrows (nāsikāgra- dṛṣṭi) and equalising their incoming (prāṇa) and outgoing (apāna) breath (vāyu) and moving it within the nostrils (nāsābhyantaracāriṇau) (verse 27).

It is important for any student of Yoga to understand the physiology and prāṇa movements that occur in this practice.

Breathing physiology – part 1 – flow of air into the nasal passage.

First, air is sucked into the respiratory system through the nostril. How does this occur?

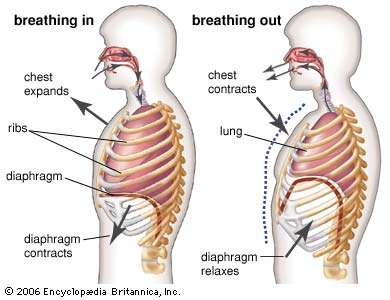

The diaphragm is a muscle which separates the abdominal cavity from the thoracic cavity. In fact, it is anchored on the lower ribs. So, during inhalation, the diaphragm moves down, creating a negative pressure in the thoracic cavity. Consequently, this draws in air from the atmosphere.

- Next, the movement of the diaphragm is against the movement of the rib cage and abdomen. So, both systems expand to allow the downward movement of the diaphragm. As a result, a reverse pressure is created within the abdomen and rib which forces the diaphragm to move upwards again. Consequently, there is an upward movement of the diaphragm which changes the intra-thoracic pressure from negative to positive, resulting in air being forced out of the lungs.

- Importantly, breathing is a reflex action. Also, it is a parasympathetic process which is controlled by the medulla oblongata. In fact, the rate of breathing is dependent on the concentration of O2 / CO2 and blood ph. Additionally, the pons controls the speed of inhalation (speed of the movement of the diaphragm).

Breathing physiology – part 2 – flow of air and awareness (prajñā).

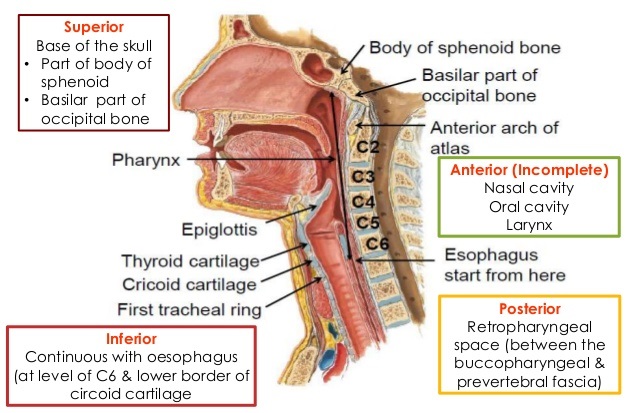

- Initially, when breathing in, air crosses the sinuses. Uniquely, sinuses are pockets of air which secrete mucous into the nasal cavity through orifice called ostia. These open into small recesses called meati and are protected by shelf like projections called turbinates.

- Next, the incoming air is compressed at the bridge of the nose, called septum. This is a venturi like structure which results in the air getting compressed when entering the nose. Therefore, due to the venturi effect in the septum, the air exits the septum into the nasal cavity under pressure which is lower than atmospheric pressure. Consequently, this causes the air to swirl within the nasal cavity.

URT Anatomy - Meanwhile, the fins of the turbinator direct the swirl and split the incoming air.

- One part of the incoming air is guided by the nasal concha over the olfactory epithelium and activates the olfactory bulb.

- Next, the inferior concha guides air over the nasopharynx. This results in a resonating column effect within the auditory tube, which activates the middle ear.

- Importantly, the sinuses are air-pockets, so they resonate to the flow of air and differential pressure between the nasal passage and sinus.

Breathing physiology – part 3 – upper respiratory tract dynamics.

The result of the above movement of air is,

- First, there is a creation of a resonance at the sphenoidal sinuses due to turbulence in the incoming swirling air flow.

- Next, the rush of air across the olfactory bulb energises the olfactory nerves and amygdala as well as the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenalin (HPA axis) and the immune system.

- Finally, the flow of air across the nasopharynx creates a vibrating column effect in the auditory canal.

All this results in an awareness of being alive.

There is a slight drop in temperature of the incoming air due to the venture effect, which is compensated by the warm air in the nasal cavity and sinuses. This is why, there is often condensate over the bridge of the nose and, also the reason for the nose being the coldest part of the face.

When the yogī equalises the incoming and outgoing breath at the nasal cavity, the air flow gets regulated to one where turbulence is slowly minimised and then made insignificant. As a result, the main senses of touch, smell and hearing are shut down. When the yogī focuses his awareness by gazing between the eyebrows, sight is also brought under control. This is why the above verse 27 is so important.

School of Yoga posits some contradictions to accepted positions.

- Availability of free-will is critical for renunciation.

- The ability to control free-will in action is limited in action (karma) because our response is controlled by conditioning (dharma).

- Increase of free-will is only possible when there is control over the movement of consciousness (citta).

- All efforts to control consciousness will be opposed by the sense of Self (puruṣa or śiva) because of fear of loss of Identity. This results in increased internal conflict, pain and a sense of dissociation from society.

- However, this effort also increases awareness of the Self (prajñā), discrimination between permanent and impermanent (viveka) and dispassion (vairāgya).

- Consequently, free-will increases.

School of Yoga explains Śrīmad-bhagavad-gītā, chapter 5, sannyāsa-yoga.

Lessons learned.

Sannyāsa is easier said than done. It requires effort, sacrifice and ability to endure pain and grief.

The transliteration and translation of Śrīmad-bhagavad-gītā, chapter 5 – sannyāsa-yoga follows.

The Saṃskṛtaṃ words are in red italics.

अर्जुन उवाच ।

संन्यासं कर्मणां कृष्ण पुनर्योगं च शंससि ।

यच्छ्रेय एतयोरेकं तन्मे ब्रूहि सुनिश्चितम् ॥ ५-१॥

Arjuna said (1) On the one hand you praise renunciation of action and at the same time recommend its performance. So, tell me conclusively, between these, which is better? (saṃnyāsaṃ karmaṇāṃ kṛṣṇa punaryogaṃ ca śaṃsasi । yacchreya etayorekaṃ tanme brūhi suniścitam ॥ 5-1॥).

श्रीभगवानुवाच ।

संन्यासः कर्मयोगश्च निःश्रेयसकरावुभौ ।

तयोस्तु कर्मसंन्यासात्कर्मयोगो विशिष्यते ॥ ५-२॥

ज्ञेयः स नित्यसंन्यासी यो न द्वेष्टि न काङ्क्षति ।

निर्द्वन्द्वो हि महाबाहो सुखं बन्धात्प्रमुच्यते ॥ ५-३॥

Śrī Kṛṣṇa said (2-3) Both renunciation and performance of action lead to the highest bliss but of the two, renunciation of action is superior to merger with action (saṃnyāsaḥ karmayogaśca niḥśreyasakarāvubhau । tayostu karmasaṃnyāsātkarmayogo viśiṣyate ॥ 5-2॥). Know this that he is a complete ascetic who neither hates nor desires, is free from opposites, truly that person becomes free from bondage easily (jñeyaḥ sa nityasaṃnyāsī yo na dveṣṭi na kāṅkṣati । nirdvandvo hi mahābāho sukhaṃ bandhātpramucyate ॥ 5-3॥).

साङ्ख्ययोगौ पृथग्बालाः प्रवदन्ति न पण्डिताः ।

एकमप्यास्थितः सम्यगुभयोर्विन्दते फलम् ॥ ५-४॥

यत्साङ्ख्यैः प्राप्यते स्थानं तद्योगैरपि गम्यते ।

एकं साङ्ख्यं च योगं च यः पश्यति स पश्यति ॥ ५-५॥

संन्यासस्तु महाबाहो दुःखमाप्तुमयोगतः ।

योगयुक्तो मुनिर्ब्रह्म नचिरेणाधिगच्छति ॥ ५-६॥

(4-6) The harmonisation of knowledge philosophy is distinct and only the childish speak of them not the learned even though when one is established then truly fruits of both are obtained (sāṅkhyayogau pṛthagbālāḥ pravadanti na paṇḍitāḥ । ekamapyāsthitaḥ samyagubhayorvindate phalam ॥ 5-4॥). The philosophical state obtained by yogīs is also reached when one that sees knowledge also sees action (yatsāṅkhyaiḥ prāpyate sthānaṃ tadyogairapi gamyate । ekaṃ sāṅkhyaṃ ca yogaṃ ca yaḥ paśyati sa paśyati ॥ 5-5॥). Renunciation is painful to obtain without implementation of yoga but when harmonised in yoga, the ascetic quickly goes to Brahman (saṃnyāsastu mahābāho duḥkhamāptumayogataḥ । yogayukto munirbrahma nacireṇādhigacchati ॥ 5-6॥).

योगयुक्तो विशुद्धात्मा विजितात्मा जितेन्द्रियः ।

सर्वभूतात्मभूतात्मा कुर्वन्नपि न लिप्यते ॥ ५-७॥

नैव किञ्चित्करोमीति युक्तो मन्येत तत्त्ववित् ।

पश्यञ्शृण्वन्स्पृशञ्जिघ्रन्नश्नन्गच्छन्स्वपञ्श्वसन् ॥ ५-८॥

प्रलपन्विसृजन्गृह्णन्नुन्मिषन्निमिषन्नपि ।

इन्द्रियाणीन्द्रियार्थेषु वर्तन्त इति धारयन् ॥ ५-९॥

(7-9) A purified soul is harmoniously merged and becomes a victorious soul when it has subdued the senses (yogayukto viśuddhātmā vijitātmā jitendriyaḥ ।), that soul which sees sentient souls in all souls when acting is also not tainted (sarvabhūtātmabhūtātmā kurvannapi na lipyate ॥ 5-7॥). I do not do anything is what the yogī who knows the Truth should cognise even when he is seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, eating, sleeping, breathing, speaking, evacuating, holding, opening the eyes, closing the eyes also. (naiva kiñcitkaromīti yukto manyeta tattvavit । paśyañśaṛṇvanspṛśañjighrannaśnangacchansvapañśvasan ॥ 5-8॥ pralapanvisṛjangṛhṇannunmiṣannimiṣannapi ।). In fact, his senses move separated from sense objects (indriyāṇīndriyārtheṣu vartanta iti dhārayan ॥ 5-9॥).

ब्रह्मण्याधाय कर्माणि सङ्गं त्यक्त्वा करोति यः ।

लिप्यते न स पापेन पद्मपत्रमिवाम्भसा ॥ ५-१०॥

कायेन मनसा बुद्ध्या केवलैरिन्द्रियैरपि ।

योगिनः कर्म कुर्वन्ति सङ्गं त्यक्त्वात्मशुद्धये ॥ ५-११॥

(10-11) He who has based his actions in the Brahman and who acts after abandoning all attachment (brahmaṇyādhāya karmāṇi saṅgaṃ tyaktvā karoti yaḥ ।), he is not tainted by consequences and is like a lotus leaf in water (lipyate na sa pāpena padmapatramivāmbhasā ॥ 5-10॥). The yogī performs action using the body, cognitive apparatus, logical reasoning, senses; abandoning attachment and acting for purification of the Soul (kāyena manasā buddhyā kevalairindriyairapi । yoginaḥ karma kurvanti saṅgaṃ tyaktvātmaśuddhaye ॥ 5-11॥).

युक्तः कर्मफलं त्यक्त्वा शान्तिमाप्नोति नैष्ठिकीम् ।

अयुक्तः कामकारेण फले सक्तो निबध्यते ॥ ५-१२॥

सर्वकर्माणि मनसा संन्यस्यास्ते सुखं वशी ।

नवद्वारे पुरे देही नैव कुर्वन्न कारयन् ॥ ५-१३॥

(12-13) Having merged with abandonment of fruits of action he obtains highest peace (yuktaḥ karmaphalaṃ tyaktvā śāntimāpnoti naiṣṭhikīm ।). However, he that is driven by desire and clings to outcome is bound to karma (ayuktaḥ kāmakāreṇa phale sakto nibadhyate ॥ 5-12॥). So, he that has detached cognition from all action controls happiness (sarvakarmāṇi manasā saṃnyasyāste sukhaṃ vaśī ।), resting in the ramparts of his nine-gated city, not acting, nor causing action (navadvāre pure dehī naiva kurvanna kārayan ॥ 5-13॥).

न कर्तृत्वं न कर्माणि लोकस्य सृजति प्रभुः ।

न कर्मफलसंयोगं स्वभावस्तु प्रवर्तते ॥ ५-१४॥

नादत्ते कस्यचित्पापं न चैव सुकृतं विभुः ।

अज्ञानेनावृतं ज्ञानं तेन मुह्यन्ति जन्तवः ॥ ५-१५॥

(14-15) Brahman is neither the initiator nor the doer in the created world, also not driven by the embrace of the union of desire for fruits with inherent personality (na kartṛtvaṃ na karmāṇi lokasya sṛjati prabhuḥ । na karmaphalasaṃyogaṃ svabhāvastu pravartate ॥ 5-14॥). Brahman does not accept of anyone their demerits or even merit (nādatte kasyacitpāpaṃ na caiva sukṛtaṃ vibhuḥ ।), this occurs on account of ignorance shrouding knowledge in deluded people (ajñānenāvṛtaṃ jñānaṃ tena muhyanti jantavaḥ ॥ 5-15॥).

ज्ञानेन तु तदज्ञानं येषां नाशितमात्मनः ।

तेषामादित्यवज्ज्ञानं प्रकाशयति तत्परम् ॥ ५-१६॥

तद्बुद्धयस्तदात्मानस्तन्निष्ठास्तत्परायणाः ।

गच्छन्त्यपुनरावृत्तिं ज्ञाननिर्धूतकल्मषाः ॥ ५-१७॥

(16-17) Wisdom destroys ignorance of anyone the Soul shines like the Sun with highest knowledge (jñānena tu tadajñānaṃ yeṣāṃ nāśitamātmanaḥ । teṣāmādityavajjñānaṃ prakāśayati tatparam ॥ 5-16॥). Those with intellect absorbed in that, Soul established in that, with focus on that, with that for the goal go without return when wisdom removes all impurities (tadbuddhayastadātmānastanniṣṭhāstatparāyaṇāḥ । gacchantyapunarāvṛttiṃ jñānanirdhūtakalmaṣāḥ ॥ 5-17॥).

विद्याविनयसम्पन्ने ब्राह्मणे गवि हस्तिनि ।

शुनि चैव श्वपाके च पण्डिताः समदर्शिनः ॥ ५-१८॥

इहैव तैर्जितः सर्गो येषां साम्ये स्थितं मनः ।

निर्दोषं हि समं ब्रह्म तस्माद् ब्रह्मणि ते स्थिताः ॥ ५-१९॥

(18-19) Those endowed with knowledge and humility will view a Brahmana, cow, elephant, dog, and even an outcast, and learned people with equal gaze, (vidyāvinayasampanne brāhmaṇe gavi hastini । śuni caiva śvapāke ca paṇḍitāḥ samadarśinaḥ ॥ 5-18॥). Thus, even they conquer creation by which inequality is established, the cognition remains spotless, consequently the equal Brahman is therefore established in Brahman (ihaiva tairjitaḥ sargo yeṣāṃ sāmye sthitaṃ manaḥ । nirdoṣaṃ hi samaṃ brahma tasmād brahmaṇi te sthitāḥ ॥ 5-19॥).

न प्रहृष्येत्प्रियं प्राप्य नोद्विजेत्प्राप्य चाप्रियम् ।

स्थिरबुद्धिरसम्मूढो ब्रह्मविद् ब्रह्मणि स्थितः ॥ ५-२०॥

बाह्यस्पर्शेष्वसक्तात्मा विन्दत्यात्मनि यत्सुखम् ।

स ब्रह्मयोगयुक्तात्मा सुखमक्षयमश्नुते ॥ ५-२१॥

(20-21) Importantly, one should not rejoice at obtaining a favourable outcome, nor grieve when an unfavourable outcome (na prahṛṣyetpriyaṃ prāpya nodvijetprāpya cāpriyam ।), with steady intellect that is undeluded, one that has knowledge of Brahman get established in the Brahman (sthirabuddhirasammūḍho brahmavid brahmaṇi sthitaḥ ॥ 5-20॥). The detached soul, when dealing with external contacts, finds within the Self, that infinite happiness as one that has merged with the Brahman enjoys (bāhyasparśeṣvasaktātmā vindatyātmani yatsukham । sa brahmayogayuktātmā sukhamakṣayamaśnute ॥ 5-21॥).

ये हि संस्पर्शजा भोगा दुःखयोनय एव ते ।

आद्यन्तवन्तः कौन्तेय न तेषु रमते बुधः ॥ ५-२२॥

शक्नोतीहैव यः सोढुं प्राक्शरीरविमोक्षणात् ।

कामक्रोधोद्भवं वेगं स युक्तः स सुखी नरः ॥ ५-२३॥

(22-23) In fact, all outcomes born from external contact, they cause suffering only (ye hi saṃsparśajā bhogā duḥkhayonaya eva te ।) they have a beginning as well as an end, so wise people do not find delight in them (ādyantavantaḥ kaunteya na teṣu ramate budhaḥ ॥ 5-22॥). Anyone who can withstand before liberation from the body, impulses born of desire and anger, he becomes united with Brahman, he is a happy man (śaknotīhaiva yaḥ soḍhuṃ prākśarīravimokṣaṇāt । kāmakrodhodbhavaṃ vegaṃ sa yuktaḥ sa sukhī naraḥ ॥ 5-23॥).

योऽन्तःसुखोऽन्तरारामस्तथान्तर्ज्योतिरेव यः ।

स योगी ब्रह्मनिर्वाणं ब्रह्मभूतोऽधिगच्छति ॥ ५-२४॥

लभन्ते ब्रह्मनिर्वाणमृषयः क्षीणकल्मषाः ।

छिन्नद्वैधा यतात्मानः सर्वभूतहिते रताः ॥ ५-२५॥

कामक्रोधवियुक्तानां यतीनां यतचेतसाम् ।

अभितो ब्रह्मनिर्वाणं वर्तते विदितात्मनाम् ॥ ५-२६॥

(24-26) Who finds happiness within, even who has internal pleasure from illumination from Brahman, that yogī attains absolute freedom and merges with Brahman (yo’ntaḥsukho’ntarārāmastathāntarjyotireva yaḥ । sa yogī brahmanirvāṇaṃ brahmabhūto’dhigacchati ॥ 5-24॥). ṛṣis (seers) achieve absolute freedom due to cleaning of impurities, cutting of duality, rejoicing in the welfare of all beings (labhante brahmanirvāṇamṛṣayaḥ kṣīṇakalmaṣāḥ । chinnadvaidhā yatātmānaḥ sarvabhūtahite ratāḥ ॥ 5-25॥). Detached from desire and anger ascetics control their consciousness in all situations (abhitaḥ = on all sides), are evolved souls who exist in absolute freedom (kāmakrodhaviyuktānāṃ yatīnāṃ yatacetasām । abhito brahmanirvāṇaṃ vartate viditātmanām ॥ 5-26॥).

स्पर्शान्कृत्वा बहिर्बाह्यांश्चक्षुश्चैवान्तरे भ्रुवोः ।

प्राणापानौ समौ कृत्वा नासाभ्यन्तरचारिणौ ॥ ५-२७॥

यतेन्द्रियमनोबुद्धिर्मुनिर्मोक्षपरायणः ।

विगतेच्छाभयक्रोधो यः सदा मुक्त एव सः ॥ ५-२८॥

भोक्तारं यज्ञतपसां सर्वलोकमहेश्वरम् ।

सुहृदं सर्वभूतानां ज्ञात्वा मां शान्तिमृच्छति ॥ ५-२९॥

(27-29) Excluding external stimuli outside bring gaze inside between the eyebrows (sparśānkṛtvā bahirbāhyāṃścakṣuścaivāntare bhruvoḥ ।). Then, equalise inhalation and exhalation, moving it within the nostrils (prāṇāpānau samau kṛtvā nāsābhyantaracāriṇau ॥ 5-27॥). With the senses, cognition and logical apparatus of the sage are focused on liberation, desire, fear, anger leave and he forever and truly becomes free (yatendriyamanobuddhirmunirmokṣaparāyaṇaḥ । vigatecchābhayakrodho yaḥ sadā mukta eva saḥ ॥ 5-28॥). He enjoys fruits of his austerity and becomes Lord of all worlds who is affectionate to all creation and comes to me in peace (bhoktāraṃ yajñatapasāṃ sarvalokamaheśvaram । suhṛdaṃ sarvabhūtānāṃ jñātvā māṃ śāntimṛcchati ॥ 5-29॥).